Gustave Whitehead - Picture

More Aviation History

|

|

Gustave Whitehead

Full name: Gustave Albin Whitehead

Born: January 1, 1874(1874-01-01)

Leutershausen, Bavaria

Died: October 10, 1927(1927-10-10) (aged 53)

Cause of death: Heart attack

Nationality: German

Spouse: Louise Tuba Whitehead

Aviation career:

Known for: Claimed flights before Wright brothers

First flight: August 14, 1901 (reportedly)

Number 21

Gustave Albin Whitehead, born Gustav Albin Weisskopf (January 1, 1874 - October 10, 1927) was an aviation pioneer who immigrated from Germany to the U.S., where he designed and built early flying machines and engines to power them.

In August 1901 a newspaper reported that he made a powered controlled flight in Connecticut-two years before the Wright brothers flew. He personally claimed credit for the feat, and he and eyewitnesses claimed he made several other powered flights in the state that year and in 1902. No further reports or claims of powered flights were made for him after 1902, and publicity faded for his aeronautical work, which lasted from about 1897 to 1911. He lapsed into obscurity until a 1935 magazine article and a 1937 book focused attention on his life and led to "lively debate" among scholars, researchers, aviation enthusiasts and even Orville Wright on the question of whether Whitehead actually flew. Research in the 1960s and 70s and books in 1966 and 1978 led to renewed debate and controversy. Enthusiasts in the U.S. and Germany have built working replicas of Whitehead's 1901 flying machine.

Early life and career

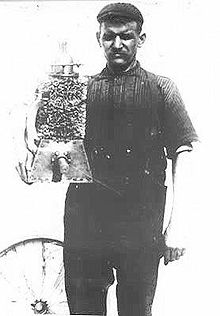

Picture - Gustave Whitehead with an early engine

Whitehead was born in Leutershausen, Bavaria, the second child of Karl Weisskopf and his wife Babetta. As a boy, he showed an interest in flight, experimenting with kites and earning the nickname "the flyer". He and a friend caught and tethered birds in an attempt to learn how they flew, an activity which police soon stopped. His parents died in 1886 and 1887, when he was a boy. He then trained as a mechanic and traveled to Hamburg, where in 1888 he was forced to join the crew of a sailing ship. A year later, he returned to Germany, then journeyed with a family to Brazil. He went to sea again for several years, learning more about wind, weather and bird flight.

Weisskopf arrived in the U.S. in 1893. He soon anglicized his name to Gustave Whitehead.

In 1897 the Aeronautical Club of Boston hired Whitehead to build two gliders, one of which was partially successful and in which Whitehead flew short distances, and toy manufacturer E. J. Horsman in New York hired Whitehead to build and operate advertising kites, and model gliders. Whitehead occupied himself with plans to provide a motor to drive one of his gliders.

Flight claims

Pittsburgh 1899

According to an affidavit given in 1934 by Louis Darvarich, a friend of Whitehead, the two men made a motorized flight together of about half a mile in Pittsburgh's Schenley Park in April or May 1899. Darvarich said they flew at a height of 20 to 25 ft (6.1 to 7.6 m) in a steam-powered monoplane aircraft and crashed into a three-story building. Darvarich said he was stoking the boiler aboard the craft and was badly scalded in the accident, requiring several weeks in a hospital. Reportedly, because of this incident, Whitehead was forbidden to do any more flight experiments in Pittsburgh.

Whitehead and Darvarich traveled to Bridgeport, Connecticut to find factory jobs.

Connecticut 1901

The aviation event for which Whitehead is now best-known reportedly took place in Fairfield, Connecticut on August 14, 1901. According to an eyewitness newspaper article widely attributed to journalist Dick Howell of the Bridgeport Sunday Herald, Whitehead piloted his Number 21 aircraft in a controlled powered flight for about half a mile up to 50 feet high and landed safely. The feat, if true, preceded the Wright brothers by more than two years and exceeded their best 1903 Kitty Hawk flight, which covered 852 feet at a height of about 10 feet.

The Sunday Herald article was published on August 18, 1901. Information from the article was also reprinted in the New York Herald and Boston Transcript. No photographs were taken, but a drawing of the aircraft flying accompanied the Sunday Herald article. Whitehead subsequently claimed he made four "trips" in the airplane on August 14, 1901; and that the longest was one and a half miles.

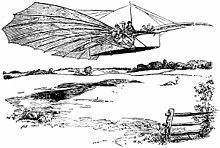

Picture - The drawing which accompanied the article in the August 18, 1901, Sunday Herald

The Sunday Herald reported that before attempting to pilot the aircraft, Whitehead successfully test flew it unmanned in the pre-dawn hours, using tether ropes and sandbag ballast. When Whitehead was ready to make a manned flight, the article said: "By this time the light was good. Faint traces of the rising sun began to suggest themselves in the east."

The newspaper reported that trees blocked the way after the flight was in progress, and quoted Whitehead as saying, "I knew that I could not clear them by raising higher, and also that I had no means of steering around them by using the machinery." The article said Whitehead quickly thought of a solution to steer around the trees:

"He simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other. This careened the ship to one side. She turned her nose away from the clump of sprouts when within fifty yards of them and took her course around them as prettily as a yacht on the sea avoids a bar. The ability to control the air ship in this manner appeared to give Whitehead confidence, for he was seen to take time to look at the landscape about him. He looked back and waved his hand exclaiming, 'I've got it at last.'"

"He simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other. This careened the ship to one side. She turned her nose away from the clump of sprouts when within fifty yards of them and took her course around them as prettily as a yacht on the sea avoids a bar. The ability to control the air ship in this manner appeared to give Whitehead confidence, for he was seen to take time to look at the landscape about him. He looked back and waved his hand exclaiming, 'I've got it at last.'"

Picture - Junius Harworth

When Whitehead neared the end of a field, the article said he turned off the motor and the aircraft landed "so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least."

Junius Harworth, who was a boy when he was one of Whitehead's helpers, said Whitehead flew the airplane at another time in the summer of 1901 along the edge of property belonging to the local gas company. Upon landing, Harworth said, the machine was turned around and another hop was made back to the starting point.

During this period Whitehead also reportedly tested an unmanned and unpowered flying machine, towed by men pulling ropes. A witness said the aircraft rose above telephone lines, flew across a road and landed undamaged. The distance covered was later measured out at around 1,000 ft (305 m).

Connecticut 1902

Whitehead claimed two spectacular flights on January 17, 1902 in his improved Number 22, with a 40 Horsepower (30 kilowatt) motor instead of the 20 hp (15 kW) used in the Number 21, and aluminum instead of bamboo for structural components. In two published letters he wrote to American Inventor magazine, Whitehead said the flights took place over Long Island Sound. He said the distance of the first flight was about two miles (3 kilometers) and the second was seven miles (11 km) in a circle at heights up to 200 ft (61 m). He said the airplane, which had a boat-like fuselage, landed safely in the water near the shore

For steering, Whitehead said he varied the speed of the two propellers and also used the aircraft rudder. He said the techniques worked well on his second flight and enabled him to fly a big circle back to the shore where his helpers waited. He expressed pride in the accomplishment: "...as I successfully returned to my starting place with a machine hitherto untried and heavier than air, I consider the trip quite a success. To my knowledge it is the first of its kind. This matter has so far never been published."

In his first letter to American Inventor, Whitehead stated his claim of flying in the summer of 1901 He added, "This coming Spring I will have photographs made of Machine No. 22 in the air." He said snapshots, apparently taken during his claimed flights of January 17, 1902 "did not come out right" because of cloudy and rainy weather. The magazine editor replied that he and readers would "await with interest the promised photographs of the machine in the air," but there were no further letters nor any photographs from Whitehead.

A description of a Whitehead aircraft as remembered 33 years later by his brother John Whitehead gave information related to steering:

"Rudder was a combination of horizontal and vertical fin-like affair, the principle the same as in the up-to-date airplanes. For steering there was a rope from one of the foremost wing tip ribs to the opposite, running over a pulley. In front of the operator was a lever connected to a pulley: the same pulley also controlled the tail rudder at the same time."

"Rudder was a combination of horizontal and vertical fin-like affair, the principle the same as in the up-to-date airplanes. For steering there was a rope from one of the foremost wing tip ribs to the opposite, running over a pulley. In front of the operator was a lever connected to a pulley: the same pulley also controlled the tail rudder at the same time."

John Whitehead arrived in Connecticut from California in April 1902, intending to help his brother. He did not see any of his brother's aircraft in powered flight.

A 1935 article in Popular Aviation magazine, which renewed interest in Whitehead, said winter weather ruined the Number 22 airplane after Whitehead placed it unprotected in his yard following his claimed flights of January 1902. The article said Whitehead did not have money to build a shelter for the aircraft because of a quarrel with his financial backer. The article also reported that in early 1903 Whitehead built a 200 horsepower eight-cylinder engine, intended to power a new aircraft. Another financial backer insisted on testing the engine in a boat on Long Island Sound, but lost control and capsized, sending the engine to the bottom.

Aerial machines

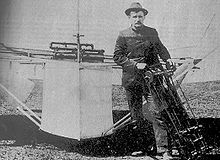

Picture - The No. 21 aircraft. Whitehead sits beside it with daughter Rose in his lap; others in the photo are not identified. A pressure-type engine rests on the ground in front of the group.

Whitehead's Number 21 monoplane had a wingspan of 36 ft (11 m). The fabric covered wings were ribbed with bamboo, supported by steel wires and were very similar to the shape of the Lilienthal glider's wings. The arrangement for folding the wings also closely followed the Lilienthal design. The craft was powered by two engines: a ground engine of 10 hp (7.5 kW), intended to propel the front wheels to reach takeoff speed, and a 20 hp (15 kW) acetylene engine powering two propellers, which were designed to counter-rotate for stability.

Whitehead owned and read a copy of Octave Chanute's famed 1894 "Progress in Flying Machines." Chanute detailed D'Esterno's design, along with a top view drawing of the machine, which was not built. The design of Whitehead's No. 21 1899-1901 monoplane shared many important features with the design of Count D'Esterno's 1864 monoplane glider and Penaud and Gauchot's 1876 monoplane.

Picture - Whitehead piloting his glider of 1903

Whitehead described his No. 22 aircraft and compared some of its features to the No. 21 in a letter he wrote to the editor of American Inventor magazine, published April 1, 1902. He said the No. 22 had a five-cylinder 40 hp kerosene motor of his own design, weighing 120 lbs. He said ignition was "accomplished by its own heat and compression." He described the aircraft as 16 feet long, made mostly of steel and aluminum with wing ribs made of steel tubing, rather than bamboo, which was used in the Number 21 aircraft. He explained that the two front wheels were connected to the kerosene motor, and the rear wheels were used for steering while on the ground. He said the wing area was 450 square feet, and the covering was "the best silk obtainable." The propellers were "6 feet in diameter...made of wood...covered with very thin aluminum sheeting." He said the tail and wings could all be "folded up...and laid against the sides of the body."

Picture - Whitehead's large Albatros-type glider - ca. 1905 - 1906

Whitehead also built gliders until about 1906 and was photographed flying these machines.

Later career

In addition to his work on flying machines, Whitehead built engines. Air Enthusiast wrote:

"In fact, Weisskopf's ability and mechanical skill could have made him a wealthy man at a time when there was an ever increasing demand for lightweight engines, but he was far more interested in flying. Even so, word of his talent as a machinist spread rapidly. His daughter, Rose, remembers bringing home so many letters with orders and advance payments on engines that she could scarcely carry them. She stated that one day, her father returned 50 orders, for he built only as many engines for sale as he felt would provide him with funds to advance his own work upon airplanes."

"In fact, Weisskopf's ability and mechanical skill could have made him a wealthy man at a time when there was an ever increasing demand for lightweight engines, but he was far more interested in flying. Even so, word of his talent as a machinist spread rapidly. His daughter, Rose, remembers bringing home so many letters with orders and advance payments on engines that she could scarcely carry them. She stated that one day, her father returned 50 orders, for he built only as many engines for sale as he felt would provide him with funds to advance his own work upon airplanes."

Whitehead's business practices were unsophisticated and he was sued by a customer, resulting in a threat that his tools and equipment would be seized. He hid his engines and most of his tools in a neighbor's cellar and continued his aviation work. One of his engines was installed by aviation pioneer Charles Wittemann in a helicopter built by Lee Burridge of the Aero Club of America, but the craft failed to fly.

Whitehead's own 1911 studies of the vertical flight problem resulted in a 60-bladed helicopter, which, unmanned, lifted itself off the ground.

He lost an eye in a factory accident and also suffered a severe blow to the chest from a piece of factory equipment, an injury that may have led to increasing attacks of angina. Despite these setbacks he exhibited an aircraft at Hempstead, New York, as late as 1915. He continued to work and invent. He designed a braking safety device, hoping to win a prize offered by a railroad. He demonstrated it as a scale model but won nothing. He constructed an "automatic" concrete-laying machine, which he used to help build a road north of Bridgeport. These inventions, however, brought him no more profit than did his airplanes and engines. Around 1915 Whitehead worked in a factory as laborer and repaired motors to support his family.

With World War I came prejudice against Germans. Whitehead never lost his German accent and never acquired American citizenship.

He died of a massive heart attack, on October 10, 1927, after attempting to lift an engine out of an automobile he was repairing. He stumbled onto his front porch and into his home, then collapsed dead in the house.

Rediscovery

Whitehead's work remained almost completely unknown to the public and aeronautical community until a 1935 article in Popular Aviation magazine co-authored by Stella Randolph, an aspiring writer, and aviation history buff Harvey Phillips. Randolph expanded the article into a book, "Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead," published in 1937. Randolph sought out people who had known Whitehead and had seen his flying machines and engines. She obtained 16 affidavits from 14 people and included the text of their statements in the book. Four people said they did not see flights, while the others said they saw flights of various types, ranging from a few dozen to hundreds of feet to more than a mile.

Harvard professor John B. Crane wrote an article published in National Aeronautic Magazine in December 1936, disputing claims and reports that Whitehead flew. The following year, after further research, Crane adopted a different tone. He said, "There are several people still living in Bridgeport who testified to me under oath that they had seen Whitehead make flights along the streets of Bridgeport in the early 1900's." Crane repeated Harworth's claim of having witnessed a 1½ mile airplane flight made by Whitehead on August 14, 1901. He suggested a Congressional investigation to consider the claims. In 1949 Crane published a new article in Air Affairs magazine that supported claims that Whitehead flew.

In 1963 William O'Dwyer, a reserve U.S. Air Force major, accidentally discovered photographs of a 1910 Whitehead "Large Albatross"-type biplane aircraft (not in flight), in the attic of a Connecticut house. He then devoted himself to researching Whitehead and became convinced he had made powered flights before the Wright brothers. O'Dwyer contributed to a second book by Stella Randolph, "The Story of Gustave Whitehead, Before the Wrights Flew," published in 1966. They co-authored another book, "History by Contract," published in 1978, which criticized the Smithsonian Institution for inadequately investigating claims that Whitehead flew.

In 1968 Connecticut officially recognized Whitehead as "Father of Connecticut Aviation".

Nearly twenty years later the legislature of North Carolina, the state where Kitty Hawk is located, passed an official resolution which "repudiates" and gives "no credence" to claims for Whitehead by a "group of Connecticut residents and that State's Legislature".

Evidence

Witnesses

The Sunday Herald of Aug. 18, 1901 explicitly named two witnesses to Whitehead's reported early morning flight of August 14, 1901: "Andrew Cellie, and James Dickie, his two partners in the flying machine."

Dickie, who periodically helped Whitehead with his aeronautical work, said in a 1937 affidavit taken during Stella Randolph's research that he himself was not present at the reported flight on August 14, 1901, that he did not know Andrew Cellie, the other close associate of Whitehead who was supposed to be there, and that none of Whitehead's aircraft ever flew, to the best of his knowledge.

Dickie said he did not believe that an airplane in photographs that were shown to him ever flew. An article in Air Enthusiast countered by saying that the description Dickie gave of the airplane did not match Whitehead's Number 21.

O'Dwyer had known Dickie since childhood. Early in his research, O'Dwyer spoke by telephone to Dickie, who was older. O'Dwyer said:

He remembered me well and we kidded each other about the old days. But his mood changed to anger when I asked him about Gustave Whitehead. He flatly refused to talk about Whitehead, and when I asked him why, he said: "That SOB never paid me what he owed me. My father had a hauling business and I often hitched up the horses and helped Whitehead take his airplane to where he wanted to go. I will never give Whitehead credit for anything. I did a lot of work for him and he never paid me a dime." I noticed, though, that Dickie did not tell me he was not with Whitehead on August 14, 1901, saying simply, "I don't want to talk about it." Also, he did not say he never knew anyone named Andrew Cellie-not surprising since Cellie was Dickie's next-door neighbor on Tunis Hill in Fairfield, and they both hung around Whitehead's shop.

He remembered me well and we kidded each other about the old days. But his mood changed to anger when I asked him about Gustave Whitehead. He flatly refused to talk about Whitehead, and when I asked him why, he said: "That SOB never paid me what he owed me. My father had a hauling business and I often hitched up the horses and helped Whitehead take his airplane to where he wanted to go. I will never give Whitehead credit for anything. I did a lot of work for him and he never paid me a dime." I noticed, though, that Dickie did not tell me he was not with Whitehead on August 14, 1901, saying simply, "I don't want to talk about it." Also, he did not say he never knew anyone named Andrew Cellie-not surprising since Cellie was Dickie's next-door neighbor on Tunis Hill in Fairfield, and they both hung around Whitehead's shop.

Although he said Dickie refused to talk about Whitehead, O'Dwyer said he thought Dickie's 1937 affidavit had "little value," because of what he considered Dickie's inconsistencies with that statement when he interviewed him.

The other man who the Sunday Herald said was an eyewitness to the reported flight on August 14, 1901 was believed to be Andrew Cellie, but he could not be found in the 1930s when Randolph investigated. O'Dwyer told Aviation History that in the 1970s he searched through old Bridgeport city directories and concluded that the newspaper misspelled the man's name, which was actually Andrew Suelli, who was a Swiss or German immigrant also known as Zulli, and was Whitehead's next door neighbor before moving to the Pittsburgh area in 1902. Cellie's former neighbors in Fairfield told O'Dwyer that Cellie, who died before O'Dwyer investigated, had "always claimed he was present when Whitehead flew in 1901."

Two other persons, Junius Harworth and Anton Pruckner, who sometimes helped or worked for Whitehead, were not named in the Sunday Herald article, but gave statements decades later, also as part of Stella Randolph's research, claiming they saw Whitehead fly on August 14, 1901. In his affidavit of 1934, Harworth stated that the airplane reached a height of 200 feet and flew one and a half miles (2400m).

Also in 1934, Anton Pruckner, a tool maker who worked a few years with Whitehead, attested to the flight. Pruckner also attested to a January 1902 flight by Whitehead over Long Island Sound, but the 1988 Air Enthusiast article said "Pruckner was not present on the occasion, though he was told of the events by Weisskopf himself."

Discrepancies in statements by witnesses about different flights they said they saw on August 14, 1901, raised questions whether any flight was made. The Bridgeport Sunday Herald reported a half mile flight occurred early in the morning on August 14. Whitehead and Harworth claimed a flight one and a half miles long was made that day.

O'Dwyer organized a survey of surviving witnesses to reported Whitehead flights. Members of the Connecticut Aeronautical Historical Association (CAHA) and the 9315th Squadron (O'Dwyer's U.S. Air Force Reserve unit) went door-to-door in Bridgeport, Fairfield, Stratford, and Milford, Connecticut to track down Whitehead's long-ago neighbors and helpers. They also traced some who had moved to other parts of the state and the U.S. Of an estimated 30 persons interviewed for affidavits or on tape, 20 said they had seen flights, eight indicated they had heard of the flights, and two felt that Whitehead did not fly.

Photos

Picture - Whitehead in his working clothes

Photographs have not been found showing any of Whitehead's airplanes in flight. According to William O'Dwyer, the Bridgeport Daily Standard newspaper reported that photos showing Gustave Whitehead in successful powered flight did exist and were exhibited in the window of Lyon and Grumman Hardware store on Main Street, Bridgeport, Connecticut in October 1903.

Another missing photo that purportedly showed Whitehead in motor-driven flight was displayed in the 1906 First Annual Exhibit of the Aero Club of America at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City. The photo was mentioned in a January 27, 1906 Scientific American magazine article by aeronautical editor Stanley Beach, who helped finance Whitehead's work for several years. The article said the walls of the exhibit room were covered with a large collection of photographs showing the machines of inventors such as Whitehead, Berliner and Santos-Dumont. Other photographs showed airships and balloons in flight. The report said a single blurred photograph of a large birdlike machine propelled by compressed air constructed by Whitehead in 1901 was the only other photograph besides that of Langley's scale model machines of a motor-driven aeroplane in successful flight.

Connecticut high school science teacher Andy Kosch, who is a pilot and researched Whitehead, and Connecticut State Senator George Gunther said they heard about yet another photograph. They were told that a sea captain named Brown made a logbook entry about Whitehead flying over Long Island Sound and even photographed the airplane in flight. A friend rummaging through the attic of a house in East Lyme, Connecticut, told Kosch he found the captain's leather-bound journal containing a photo of Whitehead in flight and a description of the event. Later, when the friend learned of the journal's value, he attempted to retrieve it, but the owners had moved to California. Kosch eventually made contact with them, but they told him they could not find the journal, and the search for logbook and photograph met a dead end.

Reproductions

To show that the No.21 aircraft might have flown, Andy Kosch formed the group "Hangar 21" and led construction of an American reproduction of the craft. On December 29, 1986 Kosch made 20 flights and reached a maximum distance of 100 m (330 ft). The reproduction, dubbed "21B," was also shown at the 1986 Experimental Aircraft Association Fly-In.

In 1986, American actor and accomplished aviator Cliff Robertson, was contacted by the Hangar 21 group in Bridgeport and was asked to attempt to fly their reproduction No.21 while under tow behind a sportcar, for the benefit of the press. Robertson said "We did a run and nothing happened. And we did a second run and nothing happened. Then the wind came up a little and we did another run and, sure enough, I got her up and flying. Then we went back and did a second one." Robertson commented, "We will never take away the rightful role of the Wright Brothers, but if this poor little German immigrant did indeed get an airplane to go up and fly one day, then let's give him the recognition he deserves."

On February 18, 1998 another reproduction was flown 500 m in Germany.

Controversy

The Herald article and drawing

The writer of the Whitehead article in the Bridgeport Sunday Herald of August 18, 1901 is widely believed to have been sports editor Richard Howell, but no byline appeared on the article. In 1937 Stella Randolph stated in her first book that the author of the article was Richard Howell.

O'Dwyer believed that Howell made the drawing of the No. 21 in flight, saying that Howell was "an artist before he became a reporter." O'Dwyer spent hours in the Bridgeport Library studying virtually everything Howell wrote. O'Dwyer said: "Howell was always a very serious writer. He always used sketches rather than photographs with his features on inventions. He was highly regarded by his peers on other local newspapers. He used the florid style of the day, but was not one to exaggerate. Howell later became the Herald's editor."

Kosch said, "If you look at the reputation of the editor of the Bridgeport Herald in those days, you find that he was a reputable man. He wouldn't make this stuff up."

The Sunday Herald article was published August 18, 1901, four days after the event it described. According to Aviation History, Whitehead detractors, including Orville Wright, used the delay in publication to cast doubt on the story, questioning why the newspaper would wait four days before reporting such important news. Orville Wright's critical comments were later quoted by the both the Smithsonian Institution and by British aviation historian Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith. Aviation History explained that the Bridgeport Sunday Herald was a weekly newspaper published only on Sundays.

Mrs. Whitehead and skeptics

An early source of ammunition for both sides of the debate was a 1940 interview of Whitehead's wife Louise. The Bridgeport Sunday Post reported that Mrs. Whitehead said her husband's first words upon returning home from Fairfield on August 14, 1901, were an excited, "Mama, we went up!" Mrs. Whitehead said her husband was always busy with motors and flying machines when he was not working in coal yards or factories. The interview quoted her as saying, "I hated to see him put so much time and money into that work." Mrs. Whitehead said her husband's aviation efforts took their toll on the family budget and she had to work to help meet expenses. She said she never saw any of her husband's reported flights.

As to whether Mrs. Whitehead resented matters, Stella Randolph wrote "Mrs. Whitehead talked very freely and frankly with the writer, who made several visits to her home, in the 1930's, and there was never any intimation that she harbored any resentment about the past."

Aviation historian Carroll Gray commented:

"Perhaps the last word in the matter should be left to Gustave Whitehead's wife, Louise Tuba Whitehead, who never recalled seeing her husband fly in his flying machines."

"Perhaps the last word in the matter should be left to Gustave Whitehead's wife, Louise Tuba Whitehead, who never recalled seeing her husband fly in his flying machines."

Peter L. Jakab of the National Air and Space Museum said:

"How strange, having solved one the world's oldest scientific/engineering problems with such spectacular success, Whitehead would neglect to mention it to his wife?".

"How strange, having solved one the world's oldest scientific/engineering problems with such spectacular success, Whitehead would neglect to mention it to his wife?".

Stanley Beach

Stanley Y. Beach was the son of the editor of Scientific American magazine and later became editor himself. His father, Frederick C. Beach, contributed thousands of dollars to support Whitehead's aeronautical work. Whitehead also built an aircraft that Stanley Beach designed. Over the years, Stanley Beach gave conflicting accounts of Whitehead's accomplishments.

According to Aviation History, writings by Beach in Scientific American referred several times to Whitehead making powered flights in 1901. The Beach comments appeared in 1906 magazine editions of January 27, November 24 and December 15, and January 25, 1908. Included were these phrases: "Whitehead in 1901 and Wright brothers in 1903 have already flown for short distances with motor-powered aeroplanes"; "Whitehead's former bat-like machine with which he made a number of flights in 1901"; "A single blurred photograph of a large bird-like machine constructed by Whitehead in 1901 was the only photo of a motor-driven aeroplane in flight".

In 1937 Stanley Beach recanted his earlier statements that Whitehead had flown, saying: "I do not believe that any of his machines ever left the ground under their own power in spite of the assertions of many persons who think they saw him fly."

O'Dwyer attributed Beach's reversal to an angry break in his relationship with Whitehead, who refused to continue working on Beach's aircraft, which Whitehead felt was improperly designed.

That analysis by O'Dwyer was contained in the Aviation History article, which asked, "Why did Beach, an enthusiastic supporter of Whitehead who liberally credited Whitehead's powered flight successes of 1901, later become a Wright devotee?" The article quoted O'Dwyer offering an answer: "Beach became a politician, rarely missing an opportunity to mingle with the Wright tide that had turned against Whitehead, notably after Whitehead's death in 1927." The article said Beach's statement, "almost totally at odds with his earlier writings," was quoted by Orville Wright and was also used by Smithsonian "as a standard and oft-quoted source for answering queries about aviation's beginnings-because it said that Gustave Whitehead did not fly."

Aviation historian Gibbs-Smith also quoted Orville's refutation of Whitehead flights, which Orville based partly on the Beach statement.

O'Dwyer, the Smithsonian and the Wrights

In 1975 O'Dwyer learned about an agreement between the Smithsonian Institution and the estate of the Wright brothers. Harold S. Miller, an executor of the Wright estate, called it a "contract". According to Aviation History, O'Dwyer pursued the matter and obtained release of the document, with help from Connecticut U.S. Senator Lowell Weicker and the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. The agreement was signed and dated in 1948. O'Dwyer said that in a 1969 conversation with Paul Garber, a Smithsonian expert on early aircraft, Garber denied that an agreement existed and said he "could never agree to such a thing."

"History by Contract," the book co-authored by O'Dwyer and Randolph, argued that the agreement unfairly suppressed recognition of Whitehead's achievements. Among its provisions, the agreement explicitly prohibited the Smithsonian from saying that anyone made a manned, powered, controlled, heavier-than-air flight before the Wright brothers. The agreement contained no mention of Whitehead and was intended to settle a long-running feud between the Wrights and the Smithsonian over official credit for the first such flight. The Smithsonian had long claimed that the 1903 Large Aerodrome "A", built under the direction of Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Langley, was the first flying machine machine "capable" of the feat.

Dr. Peter L. Jakab, chairman of the Aeronautics Division at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum (NASM), said that the agreement would not stop the Smithsonian from recognizing anyone as inventor of the airplane if indisputable evidence is found:

"We would present as accurate a presentation of the history of the invention of the airplane as possible, regardless of the consequences this might incur involving the agreement. Having said that, however, at this time, as in 1948, there is no compelling evidence that Whitehead or anyone else flew before the Wright brothers."

O'Dwyer learned the Smithsonian had published a Bibliography of Aeronautics in 1909 which included references to Whitehead. O'Dwyer said it was "hard to understand" why the Smithsonian never contacted Whitehead or his family to learn more about the flight claims.

Former Connecticut state Senator George Gunther said O'Dwyer's book ("History by Contract") was too heavy-handed. Gunther said he was having "cordial" conversations with the Smithsonian about giving credit to Whitehead, "but after O'Dwyer blasted them in his book, well, that totally turned them off."

An article titled "Did Whitehead Fly?" in the January 1988 edition of Air Enthusiast magazine took an accusatory tone toward the Smithsonian:

"The evidence amassed in his favour strongly indicates that, beyond reasonable doubt, the first fully controlled, powered flight that was more than a test "hop", witnessed by a member of the press, took place on 14 August 1901 near Bridgeport, Connecticut. For this assertion to be conclusively disproved, the Smithsonian must do much more than pronounce him a hoax while wilfully turning a blind eye to all the affidavits, letters, tape recorded interviews and newspaper clippings which attest to Weisskopf's genius."

The writer was Georg K. Weissenborn, a Professor of German at the University of Toronto. He was in communication with O'Dwyer before and after the article's publication.

Wright brothers

O'Dwyer said Octave Chanute "urged" Wilbur Wright to look into lightweight engines Whitehead was building. In a letter to Wilbur on July 3, 1901, Chanute made a single reference to Whitehead, saying: "I have a letter from Carl E. Myers, the balloon maker, stating that a Mr. Whitehead has invented a light weight motor, and has engaged to build for Mr. Arnot of Elmira 'a motor of 10 I.H.P....'"

Statements obtained by Stella Randolph in the 1930s from two of Whitehead's workers, Cecil Steeves and Anton Pruckner, claimed that the Wright brothers visited Whitehead's shop. Steeves said it was in "the early 1900's" and Prucker said it was "between 1900 and 1903" and "actually prior to 1902". The January 1988 Air Enthusiast magazine states: "Both Cecil Steeves and Junius Harworth remember the Wrights; Steeves described them and recalled their telIing Weisskopf that they had received his letter indicating an exchange of correspondence." Pruckner quoted Whitehead as saying, "Now I have told them all my secrets, and I bet they will never finance my airplane anyway." Asked in later years how he knew the two men were the Wright brothers, Pruckner replied, "They had to introduce themselves."

Orville Wright denied that he or his brother ever visited Whitehead at his shop and stated that the first time they were in Bridgeport was 1909 "and then only in passing through on the train."

Whitehead's son Charles was interviewed on a 1945 radio program, which led to another magazine article, which led to a Reader's Digest article that reached a very large audience. Orville Wright, then in his seventies, countered by writing an article, "The Mythical Whitehead Flight," which appeared in the August 1945 issue of U.S. Air Services, a publication with a far smaller, but very influential, readership.

Legacy

Opinions about Whitehead's work and accomplishments differ sharply among researchers. William O'Dwyer, Stella Randolph and Andy Kosch spent years studying Whitehead and believed firmly that he made powered flights before 1903. Researchers for a German museum about Whitehead hold similar beliefs. The Smithsonian Institution rejects claims that Whitehead flew an airplane.

Contemporary U.S. aviation researchers Louis Chmiel and Nick Engler dismiss Whitehead's work and its influence, even if new evidence is discovered showing that he flew before the Wright brothers:

"While Whitehead believers insist that he was first to fly, no one claims that his work had any effect on early aviation or the development of aeronautic science. Even if someone someday produces a photo of No. 21 in flight on August 14, 1901, it will be nothing more than a footnote, a curious anomaly in the history of aviation."

"While Whitehead believers insist that he was first to fly, no one claims that his work had any effect on early aviation or the development of aeronautic science. Even if someone someday produces a photo of No. 21 in flight on August 14, 1901, it will be nothing more than a footnote, a curious anomaly in the history of aviation."

In the 1950s British aviation historian Charles Harvard Gibbs-Smith studied The Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright at the Library of Congress, and Randolph's 1937 book, and concluded that reports of Whitehead making a successful flight in advance of the Wright brothers were fabrications. Gibbs-Smith wrote: "Unfortunately, some of those who advanced [Whitehead's] claims were more intent on discrediting the Wright brothers than on establishing facts." He said in 1960 that no "reputable" aviation historian believes Whitehead ever flew.

When Whitehead was actively working in aeronautics, he attracted attention. The Smithsonian Institution took notice of him following reports of his August 1901 flight in Connecticut. In September Charles M. Manly, chief engineer for Smithsonian Secretary Samuel Langley, who was building the manned "Aerodrome", requested that a staff clerk, F.W. Hodge, look over the Number 21 machine, then on public display in Atlantic City, New Jersey, where Hodge was staying. Manly asked Hodge to estimate the dimensions of the wings, tail and propellers, the mechanism of the propeller drive and the nature of the construction, which Manly thought might be too weak. The item Manly stated he was "more interested in than anything else" was the acetylene engine. Manly stated he believed the claims made for the machine were "fraudulent." Clerk Hodge reported the machine did not appear to be airworthy.

"In October, 1904, Professor John J. Dvorak, Professor of Physics at the University of Washington in St. Louis, announced publicly that Weisskopf was more advanced with the development of aircraft than other persons who were engaged in the work."

Stanley Beach, whose opinion eventually turned negative, nevertheless stated that Whitehead "deserves a place in early aviation, due to his having gone ahead and built extremely light engines and aeroplanes. The five-cylinder kerosene one, with which he claims to have flown over Long Island Sound-on 17 January 1902 was, I believe, the first aviation Diesel."

Interest in Whitehead's engines is indicated by recollections of his daughter Rose, who said her father received numerous orders for them and even declined some when he was too busy.

An online biography based on the O'Dwyer and Randolph books, asserts that the engine Whitehead used in Pittsburgh attracted the attention of an Australian aeronautical pioneer, Lawrence Hargrave, who in 1889 invented a rotary engine.: "This steam machine was so ingenious that several years later Lawrence Hargrave told of using miniature designs of "Weisskopf-style" steam machines, as well as the "Weisskopf System" for his model trials in Australia."

In his first letter to American Inventor magazine in 1901, Whitehead wrote that "the future of the air machine lies in an apparatus made without the gas bag, I have taken up the aeroplane and will stick to it until I have succeeded completely or expire in the attempt of so doing." Newspapers around the world had reported about Santos-Dumont's experiments with motorized and steerable gas bags for a few years when Whitehead wrote this. Whitehead's words were remarkably similar to those written in 1900 to Octave Chanute by Wilbur Wright, who said "For some years I have been afflicted with the belief that flight is possible to man. My disease has increased in severity and I feel that it will soon cost me an increased amount of money if not my life."

First flying machine

Early flight

Timeline of aviation

List of firsts in aviation

List of years in aviation

Aviation history

History by contract

Citations

Sources

History by Contract, by William J. O'Dwyer; Publisher: Fritz Majer & Sohn (West Germany), 1978; ISBN 3-922175-00-7

Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead by Stella Randolph; Publisher: Places, Inc., 1937

The Story of Gustave Whitehead, Before the Wrights Flew, by Stella Randolph; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1966

Wx¼st, Albert: Gustav Weixkopf, ich flog vor den Wrights, ISBN 3-922 175-39-2

Flugpionier Gustav Weixkopf, Legende und Wirklichkeit (legend and reality), by Werner Schwipps and Hans Holzer; Aviatic Verlag Oberhaching 2001; ISBN 3-925505-65-2

More airplanes.

Source: WikiPedia