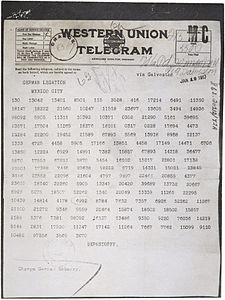

Zimmermann note - Picture

More about World War 1

|

|

Zimmermann note

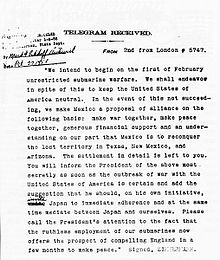

Picture - The Zimmermann Telegram as it was sent from Washington to Mexico

The Zimmermann Telegram (or Zimmermann Note) was a 1917 diplomatic proposal from the German Empire to Mexico to make war against the United States. The proposal was caught by the British before it could get to Mexico. The revelation angered the Americans and led in part to a U.S. declaration of war in April.

The message came as a coded telegram dispatched by the Foreign Secretary of the German Empire, Arthur Zimmermann, on January 16, 1917, to the German ambassador in Washington, D.C., Johann von Bernstorff, at the height of World War I. On January 19, Bernstorff, per Zimmermann's request, forwarded the telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. Zimmermann sent the telegram in anticipation of the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany on February 1, an act which German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg feared would draw the neutral U.S. into war on the side of the Allies. The telegram instructed Ambassador Eckardt that if the U.S. appeared likely to enter the war, he was to approach the Mexican Government with a proposal for military alliance. He was to offer Mexico material aid in the reclamation of territory lost during the Mexican-American War (the Southeastern section of the area of the Mexican Cession of 1848) and the Gadsden Purchase, specifically the American states of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Eckardt was also instructed to urge Mexico to help broker an alliance between Germany and the Japanese Empire.

The Zimmermann Telegram was intercepted and decoded by the British cryptographers of Room 40. The revelation of its contents in the American press on March 1 caused public outrage that contributed to the U.S.'s declaration of war against Germany and its allies on April 6.

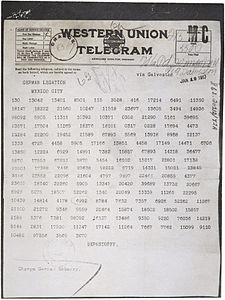

Picture - Mexican territory in 1917 (dark green), territory promised to Mexico in the Zimmermann telegram (light green), and original Mexican territory (red line)

The Telegram

Zimmermann's message was:

FROM 2nd from London # 5747. "We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President's attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace." Signed, ZIMMERMANN

Mexican response

The Telegram was part of a German effort to distract the U.S. and divert American aid going to the Triple Entente. Germany had long sought to incite a war between Mexico and the U.S., which would have tied down American forces and slowed the export of American arms.

Mexican President Venustiano Carranza assigned a general to assess the feasibility of a Mexican takeover of their former territories. The general concluded that it would not be possible or even desirable for the following reasons:

Attempting to re-take the former territories would mean unavoidable war with the much stronger U.S.

Germany's promises of "generous financial support" were empty. Mexico could not buy arms, ammunition, or other war supplies, because the U.S. was the only sizable arms manufacturer in the Americas. The British Royal Navy controlled the Atlantic sea lanes, so Germany could not be counted on to supply Mexico with war supplies directly.

Even if Mexico had the military means to win the conflict with the U.S. and re-take the area in question, Mexico would have had severe difficulty accommodating and/or pacifying the large, well-armed, English-speaking population.

Other foreign relations were at stake. Mexico had cooperated with the so-called ABC nations in South America to prevent a war with the U.S., generally improving relations all around. If Mexico were to enter war against the U.S. it would strain relations with those same ABC nations-who would later declare war on Germany.

Carranza formally declined Zimmermann's proposals on April 14, by which time the U.S. had declared war on Germany.

British interception

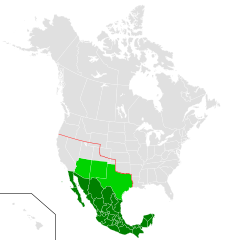

Picture - A portion of the Telegram as decrypted by the British Naval Intelligence codebreakers. Because Arizona had only been admitted to the U.S. in 1912, the word Arizona was not in the German codebook and had therefore to be split into phonetic syllables.

The Telegram was transmitted by radio and also across two telegraph routes under the cover of diplomatic messages by two neutral governments, Sweden and the U.S. Germany lacked direct telegraphic access to the Western hemisphere because the British had cut the German cables in the Atlantic and shut down German stations in neutral countries. This forced Germany to use British and American cables instead, despite the risk of interception. The Zimmermann messages passed over cables that touched on British soil, and as a result were intercepted there by British intelligence.

On the other hand, President Woodrow Wilson had granted the German diplomats permission to send their messages under the cover of U.S. diplomatic traffic in hopes that this would enable Germany to remain in touch with the U.S. and further Wilson's aims of ending the war. The Germans believed this privilege would allow them to send sensitive messages to the Western hemisphere in relative safety, since the British would be unable to use any incriminating telegram they intercepted without admitting that they were spying on American diplomatic traffic. The message passing through this way was sent from Berlin to the German ambassador in Washington, Johann von Bernstorff, for re-transmission to von Eckardt in Mexico.

The Telegram was intercepted as soon as it was sent. The codebreakers in Room 40 at the Admiralty received a copy and decrypted enough to understand the general meaning of it. The German Foreign Office encrypted the Telegram with cipher 0075, which Room 40 had partly broken. The British code breakers were able to decipher the German code thanks to codebooks seized early in the war from the SMS Magdeburg in a battle in the Gulf of Finland.

The British government wanted to use the incriminating Telegram, as it provided a splendid opportunity to draw the U.S. into World War I on the Allied side. Anti-German feeling in the U.S. was particularly strong at that moment, due to the German policy of "unrestricted" submarine warfare. But the British had two problems: they had to explain to the Americans how they got the ciphertext of the Telegram, without telling the Americans about the British intelligence operation spying on Americans' diplomatic traffic; and second, they had to have a public explanation of how they had the Telegram's deciphered text without admitting to Germany that they had broken the German code.

The British solved the first problem by also getting the ciphertext of the Telegram from the telegraph office in Mexico. The British knew that the German Embassy in Washington would relay the message by commercial telegraph, so the Mexican telegraph office would have the solved ciphertext. "Mr. H.", a British agent in Mexico, bribed an employee of the commercial telegraph company for a copy of the message (Sir Thomas Hohler, then British ambassador in Mexico, claims to have been Mr. H in his autobiography). This ciphertext could be passed to the Americans without embarrassment. The retransmission was enciphered using cipher 13040, which Britain had captured a copy of in Mesopotamia, so by mid-February the British had the complete text.

The second problem was solved by a cover story that the Telegram's deciphered text had been stolen in Mexico (The U.S. was informed that it was truly broken, but played along and backed up the cover story). The German government refused to consider a possible code break, and instead sent von Eckardt on a witch-hunt for a traitor in the embassy in Mexico.

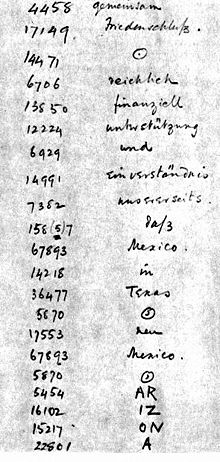

Picture - The Telegram, completely decrypted and translated

British use of the Telegram

On February 19, "Blinker" Hall, the head of Room 40, showed the Telegram to the secretary of the U.S. Embassy in Britain, Edward Bell. Bell was at first incredulous, thinking it was a forgery, then enraged. On February 20 Hall informally sent a copy to U.S. ambassador Walter Page. On February 23, Page met with Foreign Minister Balfour, and was given the ciphertext, the message in German, and the English translation. Then Page reported the story to President Woodrow Wilson, including details to be verified from telegraph company files in the U.S.

Effect in the United States

Popular sentiment in the U.S. at that time was anti-Mexican as well as anti-German, while Mexico was anti-American and in some cases, anti-European. General John J. Pershing had long been chasing the revolutionary Pancho Villa, who had carried out several cross-border raids. News of the Telegram further inflamed tensions between the U.S. and Mexico.

On the other hand, there was also a notable anti-British sentiment in the U.S., particularly among German and Irish Americans. Until the early months of 1917 American press coverage of Britain and France was not much more sympathetic than press coverage of Germany. Above all, the vast majority of Americans wished to avoid the conflict in Europe. At first, the Telegram was widely believed to be a forgery perpetrated by British intelligence. This belief, which was not restricted to pacifist and pro-German lobbies, was promoted by German and Mexican diplomats, and by some American papers, especially the Hearst press empire. Those doubts were removed by Arthur Zimmermann himself. First on March 3, 1917, and later on March 29, 1917, Zimmermann was quoted as saying "I cannot deny it. It is true."

On February 1, Germany had resumed "unrestricted" submarine warfare, which caused many civilian deaths, including American passengers on British ships. This caused widespread anti-German sentiment. The Telegram greatly increased this feeling. Besides the highly provocative anti-U.S. proposal to Mexico, the Telegram also mentioned "ruthless employment of our submarines." It was perceived as especially offensive the coded Telegram had been transmitted via the U.S. embassy in Berlin and the U.S.-operated cable from Denmark.

Historical post-script

The Telegram was not an isolated case of German-Mexican collaboration, for Germany had long sought to incite a war between Mexico and the U.S., which would have tied down American forces and slowed the export of American arms to the Allies. The Germans had engaged in a pattern of actively arming, funding and advising the Mexicans, as shown by the 1914 SS Ypiranga arms-shipping incident, and German advisors present during the 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales. The German Naval Intelligence officer Franz von Rintelen had attempted to incite a war between Mexico and the U.S. in 1915, giving Victoriano Huerta $12 million. The German saboteur Lothar Witzke, responsible for the March 1917 munitions explosion at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in the Bay Area, and possibly responsible for the July 1916 Black Tom explosion in New Jersey, was based in Mexico City. The failure of the Americans under General John J. Pershing to capture Pancho Villa in 1916, in the movement of President Carranza in favor of Germany emboldened the Germans to write the Zimmerman note.

In October 2005, it was revealed that an original typescript of the deciphered Zimmermann Telegram had recently been discovered by an unnamed historian who was researching and preparing an official history of the United Kingdom's Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). The document is believed to be the actual telegram shown to the American ambassador in London in 1917. Marked in Admiral Hall's handwriting at the top of the document are the words: "This is the one handed to Dr Page and exposed by the President." Since many of the secret documents in this incident had been destroyed, it had previously been assumed that the original typed "decrypt" was gone forever. However, after discovery of this document, the GCHQ official historian said: "I believe that this is indeed the same document that Balfour handed to Page."

American entry into World War I

Bibliography

Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40: British Naval Intelligence, 1914-1918, New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-178634-8.

Bernstorff, Count Johann Heinrich (1920). My Three Years in America, New York: Scribner's. pp. 310-311.

Boghardt, Thomas. "The Zimmermann Telegram: Diplomacy, Intelligence and The American Entry into World War I". (working papers)online edition.

Hopkirk, Peter (1994). On Secret Service East of Constantinople, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280230-5.

Katz, Friedrich. The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution. (1981).

Link, Arthur S. Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916-1917 (1965), the standard biography online at ACLS e-books.

Pommerin, Reiner (1996). "Reichstagsrede Zimmermanns (Auszug), 30. Mx¤rz 1917", in: Quellen zu den deutsch-amerikanischen Beziehungen, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. Vol. 1, pp. 213-216.

Singh, Simon The Zimmermann Telegram.

Tuchman, Barbara W. The Zimmermann Telegram (1985) excerpt and text search.

West, Nigel (1986). The SIGINT Secrets, William Morrow & Co/Quill. ISBN 0-688-09515-1.

London Daily Telegraph, 17 October 2005. Telegraph.co.uk ound, "Telegram that brought US into Great War is Found". Article by Ben Fenton.

Massie, Robert K. (2004). Castles of Steel, Vantage Books, London, 2007. ISBN 978-0-099-52378-9.

Further reading

Dugdale, Blanche (1937). Arthur James Balfour, New York: Putnam's. Vol. II, pp. 127-129.

Hendrick, Burton J. [1925] (July 2003). The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7106-X.

Kahn, David [1967] (1996). The Codebreakers, New York: Macmillan.

Winkler, Jonathan Reed (2008). Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674028395.

More aircraft.

Source: WikiPedia